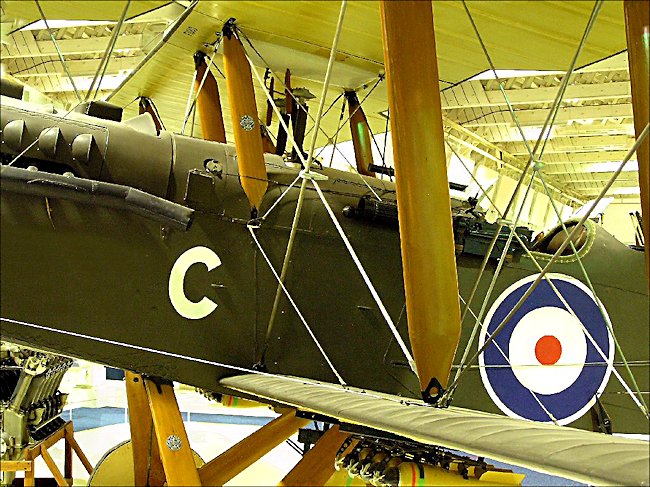

De Havilland DH9A Medium Bomber Biplane

This World War One DH9A Biplane Medium Bomber was developed by De Havilland from the under powered DH9. It entered service with the Royal Air Force RAF in 1918. It saw limited service during the end of World War One but became the backbone of the RAF post world war one colonial bombing force in the Middle East. It was known as the "Ninak" or "Nine-ack" from the designation nine-A. By the end of 1918 about 900 had been built. It was finally retired in 1931 after 13 years service.

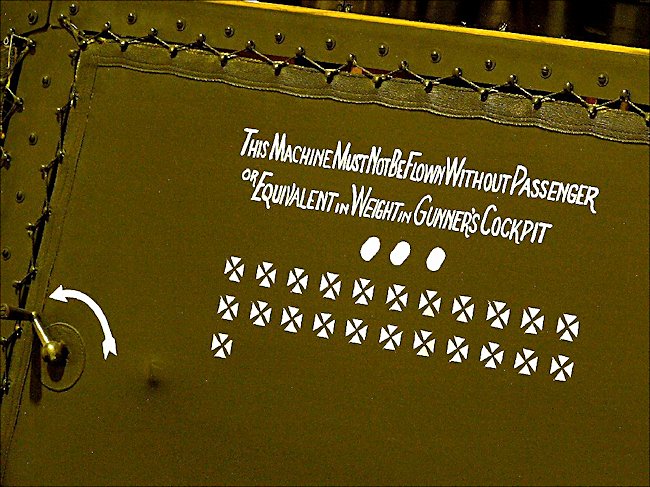

The first prototype flew in March 1918. The production aircraft were powered by a 400 hp (298 kW) American Liberty engine as production could not meet the demand for Rolls Royce engines. The De Havilland DH9A had a crew of two and was 30 foot 3 inches long. It had a maximum speed of 123 mph (198km/h). Its service ceiling was 16,750 feet (5,110m). It could stay in the air for 5 1/4 hours. It has a forward facing Vickers machine gun and one or two rear Lewis guns on a scarf ring. It could carry a maximum of 740lb (336kg) bombs under its wings and in fuselage racks.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

Deliveries to the Royal Air Force started in June 1918. In total 1,730 De Havilland DH9A were built under the wartime contracts before production ceased in 1919. It flew its first active wartime operation against a German airfield at Boulay on 14 September 1918 with No 110 Squadron RAF. The first losses of DH9a's occurred two days later during an attack on Mannheim when two of these day bombers were shot down. Later eleven machines of No. 110 Sqn bombed Frankfurt on September 25, 1918, from an altitude of 17,000ft, a height far beyond the capabilities of the older D.H.9, but four D.H.9As were shot down. Seven of the surviving light bombers returned with casualties on board; a dead observer, a wounded pilot and observer. The Squadron had been harried by German fighters all the time it was over enemy territory. During two months of operational flying 17 D.H.9As were lost by enemy action and 28 were wrecked. Most belonged to No. 110 Squadron because No. 99 Squadron was never fully re-equipped with De Havilland DH.9As.

No. 99 Squadron RAF operationally flew its first D.H.9A on 4th September 1918 but by 25th September 1918 they had only received six aircraft. It's pilots recorded their approval of the improvements on the D.H.9. They found that the D.H.9.A could carry double the bomb load and climb appreciably higher in the same given period of time. No. 99 Squadron RAF records state "It was impracticable to use the two types on a raid, and experience had proved that at least fifteen machines were necessary in order to produce daily twelve capable of crossing the lines."

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

On 28th October 1918, Captain Thorn of No. 99 Squadron RAF Manage to drop three 112-lb bombs from 15,000ft on Fresca. "Two hostile scouts, which attempted to attack, were unable to reach the D.H.9A. at that high altitude". The squadron's last recorded action was an attack on a column of motor transport at Chateau Salins, by two D.H.9As on 9th November 1918.

At the end of August 1918, No. 205 Squadron RAF. began to replace its trusty D.H.4s with DH9As. No. 18 Sqn. received its first D.H.9A 28th September 28 and had just about completed its re-equipment with the new aircraft by the time of the Armistice. The squadron records show that their D.H.9As were in action with bombing raids on Brancourt and Beaurevoir on 29th September 1918 as part of the final great Allied advance in the autumn of 1918. It also records the squadron repeatedly bombed Namur from 17,000ft with little interference from enemy fighters.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

The United States Marine Corps also adopted the DH.9A, its Northern Bombing group receiving at least 53, operations starting in September 1918. It was renamed with an American designation USD-9A. The American pilot's firepower consisted of a fixed Browning machine-gun with 750 rounds of ammunition; the gun was mounted on the starboard side of the fuselage. The Vickers gun of the British D.H.9A was on the port side. The USD-9A's observer had a pair of Lewis guns on a Scarff ring-mounting; ten 97-round drums were carried. In Russia the DH9A was produced under license for the Red Air Force.

Post World War One deployment of the De Havilland DH.9A

The DH.9A continued in service as the RAF's standard light bomber, with a total of 24 squadrons being equipped between 1920 and 1931, both at home and abroad. The first post war operations were in southern Russia in 1919, in support of the "White Army" against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. The D.H.9AS of No. 221 Squadron made a very bad start by bombing friendly forces instead of the enemy. On 10th February 1919, two of DH9As bombed a cavalry unit south of Astrakhan with one 230-lb and two 65-lb bombs. Many casualties were caused from shrapnel to the White Russian squadron of cavalry. In September 1919, the RAF personnel were ordered to return home, leaving their aircraft behind. which allowed the Reds to copy the design of the DH9A and build their own clones.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

The De Havilland DH9A medium bomber was used extensively in Iraq and the North West Frontier of India in an aerial policing role after the war. The Liberty engine was particular praise for its reliability ("as good as any Rolls Royce") in such harsh conditions. The D.H.9A's ability to cover great distances reduced the need for a large number of ground troops. A squadron of DH.9As was deployed to Turkey in response to the Chanak Crisis in 1922, but did not engage in combat. As the DH9A operated over hostile territory the DH9A's carried spare wheels, emergency rations, water and bedding.

Inevitably, a number of modifications had been made to the D.H.9A during its long service. During 1923 it was found that the joints in the mainplane spars just inboard of the ailerons had a tendency to open up. At the end of the year all aircraft were examined for this defect, and the jointed spars were replaced by one-piece members. Earlier in 1923, split-axle undercarriages were introduced. These were generally similar to the kind of undercarriage favoured by the wartime Sopwith Aviation company: each wheel was attached to a half-axle which was hinged at its inboard end, and springing was still by rubber shock-cord. Additional bracing wires ran from the fuselage to the inner ends of the half-axles. In the spring of 1925, oleo undercarriages were issued for the D.H.9As in use at flying training schools and the R.A.F. College, Cranwell. The use of this form of undercarriage was discontinued in 1927, however, and the split-axle landing-gear remained standard.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

In 1924, some of the D.H.9As of No. 207 Sqn. were fitted with R.A.E. silencers (which were possibly the outcome of the experiments which had been conducted at Farnborough with such aircraft as the S.E.5a, D.203, and the Nieuport Nighthawk, J.2415). There may have been some connection between this modification of the D.H.9As and the roughly contemporary installation of early radio-telephony equipment in the squadron's aircraft, but the silencers did not prove particularly effective as had been expected.

In 1927 the De Havilland DH9A day bomber had gone through many modifications but Flight magazine reported that it was still in service with many bombing squadrons. These are : No. 8 (Aden) ; No. 14 (Amman and Ramleh) ; No. 24 (Communications), Northolt ; No. 27 (Risalpur) ; No. 30 (Iraq) ; No. 39 (Spittlegate); No. 45 and 47 (Middle East) ; No. 55 (Iraq) ; No. 60 (Kohat) ; No. 84 (Iraq) ; No. 207 (Eastchurch) ; No. 600 (A.A.F.), Hendon ; No. 601 (A.A.F.), Hendon ; No. 602 (A.A.F.), Renfrew ; No. 603 (A.A.F.), Turnhouse ; and No. 605 (A.A.F.), Castle Bromwich.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

Some D.H.9As assisted in the evacuation of Kabul in December, 1928. The city was besieged by the rebel Kabibullah Khan. Sir Francis Humphrys, the British Envoy Extraordinary, radioed a message that he desired the evacuation of the women and children of the British Legation as soon as possible. The message ended abruptly, and communication was severed. Several gallant flights were made by D.H.9As to drop messages and signaling equipment for the Legation. The D.H.9A was used in some numbers at flying training schools and other training units, and No. 24 Sqn. had seven for communications duties. After its withdrawal from front-line squadrons the Ninak remained in service with several squadrons of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. In the Commonwealth, a few examples of the type saw service in Canada and Australia.

In 1924 Canada had nine in service and seven in storage; and Australia's D.H.9As were still in use in 1928. During the 1920s several modifications of the D.H.9A appeared. A small number of machines were fitted with the Napier Lion engine; a blunt cowling and underslung radiator were fitted. Of the Lion-powered machines, E.752 was used in deck-landing trials which were carried out on the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Eagle. A few D.H.9As were specially modified for use from aircraft carriers. To facilitate stowage on board ship, the mainplanes were made quickly detachable by the use of special wing-root fittings and a locking device. Slinging gear was fitted.

Photograph taken at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London NW9 5LL England

The Lion engine was also installed in J.6957, a D.H.9A which had an oleo undercarriage. An oleo undercarriage of a different type was tested on the Vulcan-built D.H.9A, E.9895. This was an unusually tall undercarriage made by Vickers, Ltd., and a correspondingly tall tailskid structure had to be fitted to preserve the aircraft's normal ground angle. This aircraft was also fitted with Frise-type balanced ailerons, Handley Page slots, and enormous exhaust pipes. Another interesting but little-known experimental D.H.9A was H.3588, which was fitted with a special air-cooled version of the Liberty driving a Fairey-Reed metal airscrew. The installation was an unprepossessing affair, characterized by an ugly intake, uglier outlets, and long exhaust pipes.

Several developments of the D.H.9A design were built. The first of these appeared in 1919, with the designation D.H.I5 and the official name Gazelle. This was virtually a D.H.9A airframe modified to accommodate the Galloway Atlantic engine, a V12 which was rated at 500 h.p. It will be recalled that the Galloway company had made a version of the 230 h.p. B.H.P. engine with a cast-iron cylinder block. The Atlantic was, in effect, two such engines united on a common crankcase. The first Atlantic engine appeared in 1918 and was put into production; by October 31, 1918, twenty-five engines of this type had been delivered. However, the engine underwent a process of modification analogous to that which had transformed the 230 h.p. B.H.P. (Galloway Adriatic) into the mass-produced Siddeley Puma. The transformation produced a double Puma, with aluminium cylinder blocks, which was named Siddeley Pacific.

Either the difficulties which had beset the Puma and its production had been overcome, or the authorities of the day were incapable of learning from their mistakes, for the Pacific was ordered into production on a large scale. It is not known whether it was intended to install the Pacific in the D.H.15, but it seems most probable that the aircraft was built solely as an insurance against the possible failure of the more advanced D.H.14, or Airco Okapi, a massive biplane designed as a D.H.9A replacement and powered by the then new and untried 600 h.p. Rolls-Royce Condor engine. The Armistice prevented the development of the D.H.14 by eliminating the need for it, and the D.H.15 was also abandoned. In appearance the D.H.15 resembled the D.H.9A closely, for the engine installation differed little externally from that of the Liberty. The radiator was slightly different in shape, and the Atlantic engine was fitted with long exhaust pipes which terminated beside the gunner's cockpit.

A development of rather a different kind originated in 1920 as an official design for a three-seat deck-landing naval reconnaissance aircraft based on the D.H.9A. Doubtless it was hoped to effect a substantial economy by giving carrier-borne units a modified version of the RAF.'s standard day bomber, but, as with so many adaptations of a like nature, it was not an unqualified success. The design envisaged the location of the pilot and gunner in the normal positions, and a third cockpit was provided behind the gunner's. This rearmost seat was occupied by the observer, who also had a partially-glazed ventral trough position built on below the fuselage.

The prototype aircraft was J.6585, which was apparently built by the Armstrong Whitworth company and bore the name "Tadpole" on its nose. This machine had the Liberty engine and retained a marked resemblance to the D.H.9A. The wings, tail unit, undercarriage, and basic fuselage structure of the Nine Ack were employed, but the incorporation of the third cockpit altered the appearance of the rear fuselage: the ventral "bath" was immediately conspicuous, and the top decking was modified in an ugly fashion to give depth to a cockpit which was situated at a point where the basic fuselage was relatively shallow. The entire fuselage of the Tadpole was covered with plywood, and the stagger was considerably reduced. Development of the design was entrusted to the Westland Aircraft Works, and the aircraft was named Walrus.

The ultimate product was one of the most unprepossessing aeroplanes which ever took the air. There can be little doubt that the aircraft was somewhat under-powered with the Liberty engine. The 450 h.p. Napier Lion II was substituted but its additional power can hardly have been sufficient to cope with the many drag producing modifications which were made to the Walrus. The Lion-powered production version had a modified, jettisonable undercarriage fitted with a hydrovane, and jaws for the fore-and aft arrester wires of the period were mounted on the underside of the spreader bars; emergency flotation bags, carried externally and inflated by compressed air, were fitted; and wing-folding was incorporated. A special valve on the main fuel tank permitted the rapid jettisoning of the fuel and re-sealing of the tank, which then became an additional flotation chamber. The test flying of the Walrus was performed by Capt. A. S. Keep, M.C. The aircraft was reported to be unpleasant to fly, but a batch of 36 were nevertheless ordered. One of these was later fitted with high-lift wings, horn-balanced ailerons and elevators, and an oleo 'undercarriage. By that time the Walrus had lost all resemblance to the handsome D.H.9A from which it was descended.

It will be recalled that the first aeroplane to fly with Handley Page slots was a D.H.9. That was in 1920, and in the following year there appeared the Handley Page X.4B, which later acquired the type number H.P.20. This remarkable aircraft consisted of the fuselage of a standard D.H.9A, H.634, to which a slotted cantilever monoplane wing was fitted. The X.4B was a single seater, and was flown from what would have been the rear cockpit in a standard D.H.9A fuselage. A tall undercarriage was fitted, and the aircraft weighed 6,500 lb loaded, a figure which gives some idea of the structure weight of that early cantilever wing, for the standard D.H.9A weighed only 4,645 lb with two 230-lb bombs and fuel for 51 hours.

The ultimate D.H.9A development appeared in 1926. Known as the D.H.9AJ, or Stag, this machine was built by the de Havilland Aircraft Co., and was powered by a 465 h.p. Bristol Jupiter VI engine. Differential ailerons and a neat oleo undercarriage were fitted. The Stag, which was numbered J.7028, first flew on June 15, 1926. It was perhaps fitting that the replacement for the D.H.9A was provided by the Westland Aircraft Company. Such was the official pre - occupation with economy that the Air Ministry specification required the replacement type to incorporate as many standard D.H.9A pans as possible. The Westland design, named Wapiti, first flew early in 1927. It originally embodied D.H.9A mainplanes and tail unit, and was ultimately selected for production. The Wapiti's deep fuselage made the D.H.9A fin and rudder too small, however, and they had to be replaced by larger surfaces. As production Wapitis became available they replaced the faithful old D.H.9As, which ended their service in the Auxiliary squadrons.

Unlike the D.H.9, the D.H.9A did not go into civilian use in large numbers. Very few received British civil registrations. One machine, G-EBCG, the property of the Aircraft Disposal Co., had a Rolls-Royce VIII engine, and was flown in some of the air races in the early post-war years. The D.H.9A was therefore essentially a military aeroplane, and is assured of its niche in the history of the R.A.F. The fame of the Nine Ack is secure, both as a potentially great aircraft of the First World War and as a patient, hard-working jack-of-all- trades on a more or less constant operational footing during the decade which followed the Armistice.

De Havilland DH9A Medium Bomber Biplane

Tweet